The Meanness of Production

I just finished a book by Kohei Saito called Slow Down. It originally came out in Japan in 2020 and sold a quarter of a million copies, which seems like quite a lot for a book about Marxism and what Saito calls 'degrowth communism'.

I can imagine how being released that first year of the pandemic helped it resonate with a wider audience. As terrible as those times obviously were, for me those earliest days of lockdown are also associated with a fleeting feeling of... I don't want to call it hope but perhaps... solace? Definitely not optimism, but at least a glimmer of something. Because the pandemic was real, it was serious and horrifying, and it forced the state powers of the world to show their hand and reveal that actually, they could slow down capital if they really wanted to. Things could be different, the world could pivot at extraordinary speed when the stakes were high enough. None of that lasted. Those same powers spent the following years pushing that idea back out of the public's consciousness, forcing the world back into an endless reenactment of the 'this is fine' meme.

But perhaps that sliver of time where we caught a glimpse of how the world could be made differently contributed to this book grabbing the imaginations of so many people.

WE CAN REBUILD HIM, WE HAVE THE TECHNOLOGY

The book's main argument: allowing capitalism to continue is fundamentally incompatible with civilisation surviving climate change. We must therefore transition to 'degrowth communism'. Slow down, work less, consume less, shrink economies, and so on. This view does not quite fit within a classic interpretation of Marxism that still requires all the productive forces of the world to remain chugging away in order for the workers to eventually seize them. So after setting out his broad idea, Saito spends a good chunk of the book reconstructing Marx, citing various pieces of evidence to show that Marx's thinking later in life, after writing Capital, had evolved in significant, more environmentally-aware ways.

Saito suggests that although Capital-era Marx had a kind of proto-accelerationist opinion insomuch as he claimed that the path to communism lies beyond or through capitalism, by the end of his life Marx came to realise that actually, if capitalism was left to run its course unaltered it would create a disastrous 'metabolic rift'. This is a very Pacific Rim way of him saying that the churn of endless productive industry would become so untethered from any kind of sustainability that capitalism would destroy the environment long before it destroyed itself. There'd be no world left for the workers to win.

Another way of putting this is that Marx disentangled himself from the idea of 'productivity' as a driver of change. I think what Saito means by this is that Capital-era Marx (and therefore most Marxist theory since) describes historical progress as being driven by 'productive forces'. More things, better things, more effective things, increased technological complexity, better efficiency, etc. BUT, says Saito, the later Marx, more grizzled, more bearded, realised that this productive imperative would not and could not be sustained on our fragile and finite planet. There were other ways to model 'progress', other ways to think about routes out of capitalism, and probably not destroying the planet along the way was actually quite important.

DECELERATE YRSELF

With Marx duly reconstructed into a prophetic eco-warrior, Saito dangles Aaron Bastani of Novara Media's concept of Fully Automated Luxury Communism like a kind of radical left piñata, then mercilessly smashes it to pieces with a big 'You're-Doing-Marx-Wrong' stick. Which, to be honest, I did find quite funny.

I don't mind admitting that I did enjoy the idea of Fully Automated Luxury Communism when it first start getting bandied about. I thought (and still think, to a somewhat lesser degree), that it was a useful way to think about utopias, to imagine better futures, and try to reclaim technology and various science fiction ideas from the tech bros and apply them to more egalitarian imaginaries.

Did I at any point genuinely think that this was a viable future? That asteroid mining and synthetic lab-grown meat and so on would fix the world? I am pretty sure I did not. And so this is the one area that I'm not sure I follow Saito's thinking on. Not his stance on FALC specifically — I think he is correct in his degrowth analysis — but his determination to take FALC quite so literally as an idea. I always thought it was more of a provocation, a critical thinking tool, a way to peek beyond the horizon of capitalist realism; not actually a genuine accelerationist manifesto. But perhaps that was an error on my part.

Regardless! That was a long time ago. Things change. These days I prefer to take my utopias with a side of abyssal despair rather than space-based solar farms, and I prefer my communism to be more about making sure people can have nice parks and food, less about everyone-gets-a-flying-car/let's explore space forever.

And so Saito's clear-eyed analysis is as convincing to me as it is bleak. We have to slow down. There can be no endless growth. Even 'Green Growth', can only be a transitional period, it cannot be the end goal. There is no 'good' capitalism, no 'good' economic growth. Finite planet, finite limits. Definitionally, capitalism is not equipped to deal with this. It has to be cast aside.

As Adorno said: "progress occurs only where it ends".

WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH MUSIC THOUGH?

A great question. It's the one I always end up asking myself because ultimately, I don't know how not to ask it.

65days have been round the houses thinking about 'the end of progress' since we made Wild Light, which was constructed from the ruins of an existential crisis informed by atemporality, hauntology, the slow cancellation of the future, all that postmodernity stuff that seemed so pervasive back then.

We followed that up with Decomposition Theory; not explicitly decelerationist, but could be read as an act of hitting the wall of 'progress' (i.e. where do you go after building infinite plains of endless generative music?) and instead of pushing forward regardless choosing instead to pull back, to sculpt or 'de-compose' finite chunks of discrete music from the algorithms making blurs of infinite noise.

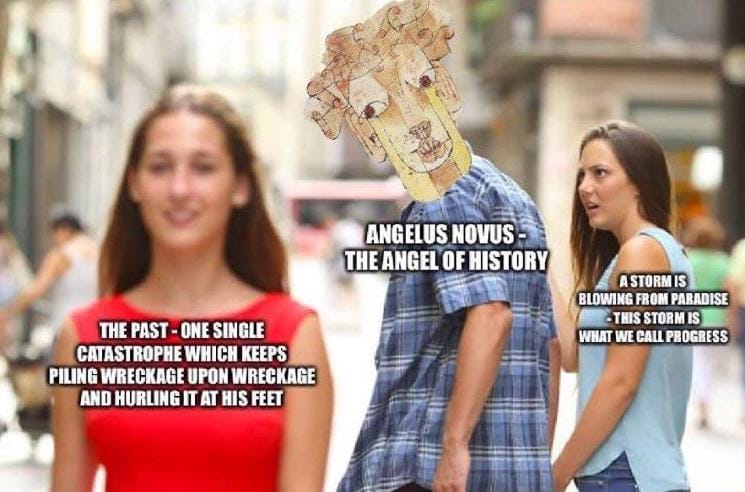

And then most recently there was replicr, 2019 and Wreckage Systems, both of which found us stumbling around in Walter Benjamin's ideas roughly cribbed from the pages of The Arcades Project and his On the Concept of History essay which features the memorable take on the Angel of History.

Perhaps a more widely-read philosopher than me could take Saito to task for his dismissal of this Benjaminian 'historical materialism' as merely a flawed view of history being driven by progress? Because I thought that Benjamin too was critical of such a thing, that the entire point of his Angel of History parable was that there are many possible histories, all necessarily always written through the perspectives and biases of the present, containing the present in them even as they cast themselves backwards? And therefore 'history as progress' was just one inaccuracy amongst many?

Also, despite the impossibility of a history built on progress/productivity, that is nevertheless the unreality we've all been living, no? That is kind of the whole problem?

I've tangled myself up here. The point is, in terms of thinking about all this in relation to music, I have been here before. And 'degrowth' as a concept is not new either. Environmentalists have been talking about this for decades; I am old enough to remember when 'contraction and convergence' was the framing of choice. Nevertheless, something about Saito's book does feel new to me and I'd like to figure out what it is and how it could be used to think about music. (And also to, y'know, save the world and bring about an actually-good communism.)

BECOME UNSTUCK IN TIME (BUT NOSTALGIA IS STILL THE ENEMY, RIGHT??)

Trying to imagine what degrowth could mean in terms of writing music brings to mind Sinners, specifically (very mild spoilers) that great sequence where a musical performance manifests both the past and future (relative to the time period of the film) of Black music, a collaboration of musical ancestors, taking part in a conversation across time and yet all under the same roof.

And perhaps there is something useful here? Because yes, new music is always informed by music that came before, but that doesn't necessarily mean 'progress', certainly not if we look at music from phenomenological or political rather than technological viewpoints. There is no serious way to argue that new music is somehow objectively 'better' than old music. It can be more familiar, perhaps more clearly tied to all the other strands of popular culture woven into our little window of existence and therefore more relatable or exciting. But just because a piece of music might have been written a hundred or a thousand years ago it doesn't mean it cannot still be affective, or danceable, or be unable to achieve whatever its original intentions were.

So perhaps music is a good lens through which to build history out of non-productive materials. All music is recycled, all music is a kind of time travel, always conversing with itself in every direction.

I vaguely gestured at this idea with the entirely made up term 'neostalgia' in THE MUSIC ABOLITIONIST PROVOCATION. A way to look back into history without lapsing into the 'nostalgia mode' Fredric Jameson warned us about. But I think I spent so much of my life being suspicious of nostalgia that, when it came to music at least, I started to become suspicious of any kind of backward momentum. I guess re-examining why I remain convinced that nostalgia is the enemy (it surely is!) might be a good place to point these thoughts next.

VAGUE CONCLUSION?

Yeah, I don't know how to wrap any of that up. I've got another draft on the go which is about the importance of being inefficient when composing. And blatantly stealing from Hegel's idea of 'good infinity' and 'bad infinity' I think there is 'good inefficiency' and 'bad inefficiency' and that this is something I find useful to think about in terms of making stuff. Now I've written whatever this is instead, I think that maybe applying the good kind of inefficiency to creative work could be a little like employing a degrowth approach? Let's see if I ever finish writing that up.

OTHER BITS & PIECES

I'll be jumping on the Live Code Stream for Palestine organised and hosted by Euler Room for a quick 15 minute set this Saturday 22nd November. My slot is at 11.45am, hopefully timed perfectly to ride my second coffee of the day caffeine wave. Dunno what I'll do yet but I imagine it will be based around my current live system. If it's any good maybe I can stick it on Bandcamp with proceeds going to Medical Aid for Palestinians or something. And if it's bad, maybe we can all just pretend it never existed and throw a bit of cash at MAP anyway.

Interview with The Verge

There's a 50% chance that this article will be paywalled for you if you click through. It is an interview with me and Paul Weir (audio guy at Hello Games and recent collaborator on the new 65daysofstatic record), ostensibly about our new album but also about generative systems and generative music.

Mainly notable because I didn't really expect the part of the conversation where I was blaming capitalism for ruining everything and going on about how much I hate generative AI to make it past The Verge's editors, but for some reason they decided that was kind of gonna be the hook of the whole article?

It is almost as if the tech press is scrambling to pretend that they were never in thrall to the AI tech bro's bluster in the first place...

Member discussion